INDIANA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY

Vol. XXI / December, 1925 / No. 4

Journal of an Emigrating Party of Pottawattomie Indians, 1938

The “consolidation” or removal of Indian Tribes from their homes to reservations further west was one of those apparently necessary and equally cruel courses dictated by the expansion of the white race in the United States. Annie H. Abel’s article, “History of Indian Consolidation West of the Mississippi” in the Annual Report of the American Historical Association, 1906, Vol. 1, describes the principal steps in the process. The so-called Removal Act, approved by President Jackson, May 28, 1830 (4 United States Statutes at Large, 411), was taken as authority for forcible removal of Indians.

In Indiana, the treaties of October 16, 1826, and October 27, 1832, followed by the activities of the United States Commissioner, Abel C. Pepper, in securing cessions of former reservations, 1834-1837, paved the way for the removal of the Potawatomis. The band, whose removal is described in the document printed herewith, lived in and near the village of Menominee, near Twin Lakes, in Marshall County. Their memory has been perpetuated by an impressive monument, between the lakes, dedicated in 1909 to Chief Menominee.

The first emigration of Potawatomis from Indiana was directed by Abel C. Pepper in 1837; the Indians were escorted by George Proffit to the place assigned them near Ft. Leavenworth, in Kansas. Later, part of them were forced to go north, up the Missouri River.

In August, 1838, the Indians at Twin Lakes were taken unawares and herded together by John Tipton and volunteer militia, chiefly from Cass County, and, with the exception of a few who temporarily escaped, were escorted to Danville, Illinois. There they were turned over to William Polke, who conducted them the rest of the way across Illinois, Missouri, and part of eastern Kansas, to their future reservation in the neighborhood of the Osage River.

William Polke, son of Charles and Christine Polke, when a child, was taken captive by Indians, with his mother and two other children, in Nelson County, Kentucky. They were kept at Detroit, their mother being ransomed by British officers. Polke was afterwards one of the founders of Plymouth, Indiana.

Dr. Jerolaman, the doctor who accompanied the Indians, was from Logansport.

Father Petit, the indefatigable Catholic missionary among the Indians of northern Indiana and southern Michigan, learning of the forced departure of this group of his charges, hurried after the band, and continued his ministrations until they reached their destination.

This journal of the emigration seems to have been written by Polke himself, but no certain proof has been found. It is printed here through the courtesy of the Ft. Wayne Public Library, which possesses the original, and the State Library, at Indianapolis, which has a photostatic copy. (315-16)

Thursday, 20th Sept.

At 3 o’clock we were up and busily preparing the discharge of the volunteers. At sun rise they were mustered and marched to Head Quarters, where, after being addressed for a few moments by the General in command, they were discharged and paid off. Sixteen of the mounted volunteers, upon a requisition of the Conductor of the emigration were retained in service and are now under the immediate charge of Ensign Smith. At 9 o’clk. a few hours before which an elderly woman died, we prepared for our march. We left the camp at half past 9, and reached our present encampment at about 2 P.M. During the march of the party, Gen. Tipton who has heretofore been in command of the volunteers, and superintended the removal of the present emigration, took his leave, and left us in charge of the Conductor, Wm. Polke, Esq. While on the march a child died on horseback. A death has also occurred since we came into camp this Evening. We are now encamped at Davis’s Point, a distance of ten miles from the camp ground of yesterday. To-morrow we expect to reach Sidney, which is reported to be a good watering place. (321-22)

Friday, 21st Sept.

Left Davis’s encampment at half-past 9. At a little before 2 we reached Sidney, near the spot selected for encampment. The health of the Indians is the same – scarcely a change – the worst of the cases in most persons proves fatal. Physician reports for yesterday, “their condition somewhat better. There are yet fifty sick in camp – three have died since my last.” The farther we get into the prairie the scarcer becomes water. Our present encampment is very poorly watered, and we are yet in the vicinity of timber. A child died since we came into camp. This morning before we left the Encampment of last night, a chief, Muk-Kose, a man remarkable for his honesty and integrity, died after a few days’ sickness. Distance traveled to-day 12 miles. Forage not so scarce as a few days ago. Bacon we occasionally procure – beef and flour, however constitute our principal subsistence. (322)

Saturday, 22nd Sept.

At 8 o’clock we left our Encampment, and entered the Prairie at Sidney. The day was exceedingly cold. The night previous had brought us quite a heavy rain, and the morning came in cold and blustery. Our journey was immediately across the Prairie, which at this point is entirely divested of timber for sixteen miles. The emigrants suffered a good deal, but still appeared to be cheerful. The health of the camp continues to improve – not a death has occurred to-day, and the cool bracing weather will go far towards recruiting the health of the invalids. A wagoner was discharged to-day for drunkenness. Dissipation is almost entirely unknown in the camp. To-night, however, two Indians were found to have possessed themselves of liquor, and become intoxicated. They were arrested and put under guard. Some six or eight persons were left at Davis’s Point this morning, for want of the means of transportation. They came in this evening. We are at present encamped at Sidoris’s Grove, sixteen miles distant from Sidney. Water quite scarce. (322)

Sunday, 23rd Sept.

Left our encampment at 9 o’clk. having been detained for an hour at the request of the Rev. W. Petit, who desired to perform service. The day was clear and cold. Our way lay across another portion of Grand Prairie, which, as was the case yesterday, we found without timber for fifteen miles. Physician reports the health of the camp still improving. “The number of sick” the report says “is forty. There have been two deaths since my last report, and four or five may be considered immediately dangerous.” A child died early this morning. One also died on the way to our present Encampment. Distance traveled to-day fifteen miles. We are now at present encamped on the Sangamon river, along the banks of which our route to-morrow lies. Subsistence, beef and flour – better, however, than usual. (322-23)

Monday, 24th Sept.

At 9 this morning we left Pyatt’s Point (the encampment of yesterday) and proceeded down the Sangamon river fifteen miles, to the place of our present Encampment, Sangamon Crossing. Physician reports “there have been two deaths since my last, and the situation of several of the sick is much worse. I would recommend that twenty-nine be left until to-morrow.” At the suggestion of Dr. Jerolaman twenty-nine persons were accordingly left behind with efficient nurses. They will join us to-morrow. We find a good deal of difficulty in procuring wagons for transportation – so many of the emigrants are ill that the teams now employed are constantly complaining of the great burthens imposed upon them in the transportation of so many sick. Subsistence and forage the same as yesterday. A child died during the evening. (323)

Tuesday, 25th Sept.

To allow the sick left at Pyatt’s Point yesterday time to join us, and to give the emigrants generally a respite, and to bring up the business of the emigration, it was determined to remain in camp to-day. The baggage wagons were weighed and reloaded during the day and the matters of the emigrants made more comfortable. Sometime in the afternoon the sick left at the encampment of yesterday arrived. Directly after their arrival a woman among the number, died. The rest were but little if any improved. A child also died this evening. The farther we advance the more sickly seems the character of the country. It is sometimes very difficult to procure provisions and forage owing to the general prostration of the husbandry… Most of the Indian men were permitted to go on a hunting excursion to-day. They brought in a considerable quantity of game. (323)

THE TRAIL OF DEATH: LETTERS OF BENJAMIN MARIE PETIT

By Irving McKee / Indiana Historical Society / 1941

Petit to John Tipton, September 3, 1838

To the Honourable General Tipton

General I received yesterday your letter dated 2nd September, to which I give to day the answer which you requested me to give you. It is not the least of the world in my power to satisfy those whom you call the dissentients, and to harmonise the whole matter, because it is not let to my choice to go, or not to go West. I am under the dependance of my Bishop and at his disposal, as much at least as any soldier of your troops is at your disposal; I wrote to him for the subject of being allowed to follow the Indians, in the case, that most of them would be willing to emigrate; I received a full denial of my request; of course I must not think any more of going West.

Was I at liberty to go or not to go, though I had no personal objection, in the case the Indians would be willing to go, it would be repugnant and hard to me to associate in any way to the unaccountable measures lately taken for the removal of the Indians. You had right perhaps, if duly authorized, to take possession of the land, but to make from free men slaves, no man can take upon himself to do so in this free country. Those who wish to move must be moved, those who want to remain must be left to themselves. Col. Pepper, in the name of the president, spoke several times in that way, and he said that by the 5th of August those who want to remain, would be submitted to the law of the country. Of course it is against men under the protection of the law, that you act in such a dictatorial manner; it is impossible for me, and for many to conceive how such events may take place in this country of liberty. I have consecrated my whole life, my whole powers to the good of my neighbours, but as to associate to any violence against them, even if it were at my own disposal, I cannot find in me strength enough to do so. May God protect them, and me, against numerous misrepresentations which are made, both of them and of me.

I am sorry, General, not to be able to comply any further with your wishes.

Your most obedient Servant

B: PETIT ptre Mre

(88-9)

Petit to Father Francois, September 23, 1838

32 Miles West of Danville 23 September, 1838

Monsieur and Dear Friend,

After these last few days of traveling I am indeed glad to have this opportunity of informing you of everything concerning us since I joined the emigration at Danville. A dozen have died, among them several Indians who were baptized in articulo mortis; exterior alleviation was given to the others, almost the entire band. Today we were better treated because of a kind of authority given me which I accepted and am using for their good.

It is indeed far from my intention to find anything to regret in Monseigneur’s decision regarding me; I think I am where I should be.

From time to time I can say Holy Mass; soon I shall have my tent all to myself and even be able to hear confession.

When we encamp I am entrusted with the sick and assigned to the doctor as interpreter. On the march I have general supervision over all and decide upon whatever can be alleviating.

If you can obtain a few days from Monseigneur to visit Pokagon, it would be the most deserving of your missions. I fear they are bewildered; you would find Mousse there. Tell him or write to him that I obtained permission to leave his baggage at Danville, but his son did not know where he was, and the heavy expenses of transportation made us decide that the cost would exceed the value of the contents. He will be paid for his oxen at the Mississippi; I shall send him the money.

Respects to everyone. Enclose this letter to Monseigneur, if you please. I have seen nothing of M. Buteaux, to whom I wanted to hand it.

I have no more time. Adieu; pray for me.

Your brother and servant in Jesus Christ,

B. PETIT

Ptre. Mre.

(95-6)

Edited by J.R. Stewart / 1918

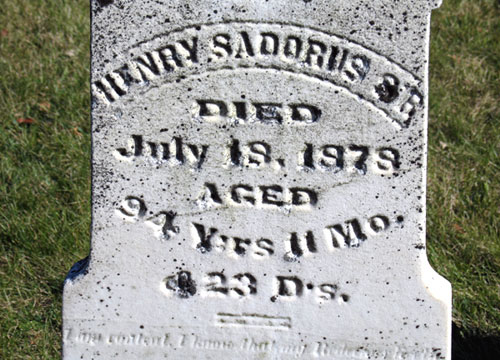

Henry Sadorus

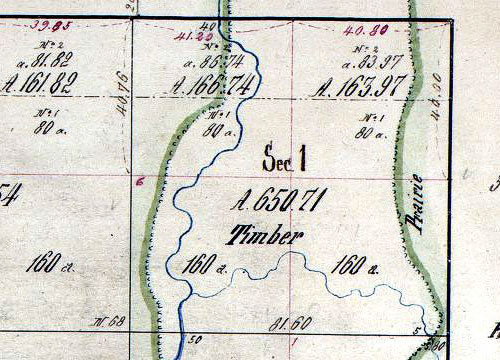

After the Fielders and Tompkinses, the next family to settle in Champaign County with any degree of permanence was that headed by Henry Sadorus, who continued to reside on the Okaw, in the southwestern part of the county, for a period of fifty-four years. He gave his name to the grove and the township, as well as the village in the extreme northeastern past of the latter. Mr. Sadorus had served as a soldier in the War of 1812, and about 1818, then thirty-five years of age, immigrated with his family to Indiana. He was a natural tradesman and money-maker, and had amassed quite a capital for the times, when he started for the Vermilion country, with his wife and six children, in 1824. The eldest of the children was a lad of fourteen, who assisted his father in managing the five yoke of steers which drew the prairie wagon toward the Okaw. It was in the fall of the year, and when he discovered an abandoned cabin on the southeast quarter of Section 1, Township 17, Range 7, he took possession of it and the family commenced housekeeping. He remained a squatter until December 11, 1834, when he entered the quarter section of at the Vandalia land office. His son, William, at the same time, entered the eighty-acre tract adjoining on the north, which were the first entries of land in Sadorus Township.

At the time of Mr. Sadorus’ death on July 18, 1878, the Champaign County Gazette published a complete and appreciative sketch of the deceased, in which occurred the following: “The State Road from Kaskaskia having been opened and passing near his residence, Mr. Sadorus decided to erect a building for a tavern. The nearest saw mill was at Covington, Indiana, sixty miles away, but the lumber (some 50,000 feet) was hauled through unbridged sloughs and streams, and the house was built. For many years Mr. Sadorus did a thriving business. His corn was disposed of to drovers who passed his place with herds of cattle for the East, besides being fed to great numbers of hogs on his farms. His first orchard, now mostly dead, consisted of fifty Milams, procured somewhere near Terre Haute, Indiana. From them were taken innumerable sprouts, and that apple became very common in this section.

In common with nearly all the pioneers, Mr. Sadorus grew his own cotton, at least enough for clothing and bedding. A half-fare sufficed for this, and the custom was kept up until it became no longer profitable, the time of the mother and three daughters being so much occupied in cooking for and waiting upon the travelers that they could not weave; besides goods began to get cheaper and nearly every immigrant had some kind of cloth to dispose of. About the year 1846 Mrs. Sadorus died, and seven years later he again married, this time a Mrs. Eliza Canterbury of Charleston.

“Some years ago, becoming tired of attending to so much business, Mr. Sadorus divided his property among his descendants, retaining, however, an interest which enabled him to pass his declining years in ease. He died full of years, respected by all who knew him, and beloved by a large circle of friends. He was kind and hospitable to strangers, and never turned a needy man away empty-handed from his door.”

Judge Cunningham adds, speaking of the old Sadorus home and Grove: “The home thus set up far from other human habitations was the abode of contentment, hospitality and reasonable thrift, in the first rude cabin which sheltered the family, as well as in the more pretentious home to which the cabin gave place in due time. The Grove was a landmark for many miles around, and the weary traveler well knew that welcome and rest always awaited him at the Sadorus home. Here Mr. Sadorus entertained his neighbors – the Buseys, Webbers and others, from Big Grove; the Piatts, Boyers and others, from down on the Sangamon; Coffeen, the enterprising general merchant, from down on the Salt Fork; the Johnsons, from Linn Grove, and the dwellers upon the Ambraw and the Okaw. He was also the counselor and advisor of all settlers along the upper Okaw in matters pertaining to their welfare, and his judgement was implicitly relied upon. (103-104)

Favorite Resort Near Sadorus

A favorite resort of the Indians upon the Okaw was a place near that stream about half a mile north of the village of Sadorus, and upon the east bank of the stream. There they often encamped in the autumn and awaited the coming of deer and other game when driven by the prairie fires from the open country into the timber. To this day the plow upon that ground turns up stone-axes and arrow heads, left there by these long-ago tenants of the prairies. The cabinet of Capt. G. W. B. Sadorus contains many of these and other relics. Even after the settlement of the country, the Indians followed the practice of here awaiting the annual coming of their prey. Many were the incidents told by the settlers about the Big Grove – few of whom yet remain – in connection with the visits made here by the Pottawattamies, which continued for many years after the first occupancy by the whites. The prairies and groves of this country, as well as the neighboring counties of Illinois, were favorite hunting grounds of the people of this tribe, whose own country was along the shores of Lake Michigan, as they had been of the former occupants and claimants, the Kickapoos, who had relinquished their rights. Not only was this region esteemed by those people on account of the game with which it abounded, but it yielded to their cultivation abundant returns in cereals and vegetables. Its winters were not so long and much less rigorous than were those of the lake regions, so that the red visitors of the pioneers of Champaign and Vermilion counties were not rarities. No complaint has come down to the inquirers of later years of any hostile or unfriendly acts from these people, but on the contrary, from all accounts they avoided doing any harm and were frequently helpful to the new comers. (89-90)

Told to “Git”

In the summer of 1832, before the organization of the county and the fixing of its county seat – when the site of Urbana was perhaps only what it had been for generations before, and Indian camping ground – a large number of Indians came and camped around the spring above alluded to as situated near the stone bridge. It happened to be at the time of the excitement caused by the Black Hawk War, and caused not a little apprehension among the few inhabitants around the Big Grove, although the presence in the company of many women and children of the Indians should have been an assurance of no hostile errand. A meeting of the white settlers was had, and the removal of the strange visitors determined upon as a measure of safety. A committee consisting of Stephen Boyd, Jacob Smith, Gabe Rice and Elias Stamey was appointed by the white settlers and charged with the duty of having a talk with the red men. The committee went to the camp and, mustering their little knowledge of their language, announced to the Indians that they must “puck-a-chee,” which they understood to be a command to them to leave the country. The order was at once obeyed. The Indians gathered up their ponies, papooses and squaws and left, greatly to the relief of the settlers. (92-93)

Miamis Passing to the West

About 1832 a large body of Indians (believed to have been Miamis), 900 in number, in moving from their Indiana reservation to the western territories, passed through Champaign County, crossing the Salt Fork at Prather’s Ford, a mile or so above St. Joseph, thence by the north side of Big Grove to Newcom’s Ford and by Cheney’s Grove. It is said the caravan extended from Prather’s Ford to Adkins’ Point, as the northern extremity of Big Grove was then called. These Indians were entirely friendly to the whites and encamped two days at the Point for rest, where the settlers gathered around for trade and to enjoy their sports. (94)

En Route to Washington

In the winter of 1852-53 came a company of braves from the West through Urbana, on their way to Washington to have a talk with the President. While stopping here one of their number died, and was buried in the old cemetery at Urbana. His comrades greatly mourned him, and planted at the head of his grave a board, upon which were divers cabalistic decorations. After committing his body to the grave, his comrades blazed a road with their tomahawks to the Bone Yard branch, to guide the dead man’s thirsty spirit to the water. (94-95)

Last of the Champaign County Indians

At stated, as late as the Black Hawk War scattered bands of Kickapoo, Pottawattamies and Delawares were still roaming through the woods and over the prairies of central and eastern Illinois, killing squirrels, wild turkeys, grouse and deer. About the 1st of March they usually returned in a body toward the Kankakee for the purpose of making maple sugar. But at the close of the war, the whites of Indiana and Illinois made a general demand upon the Government to see that all Indians were moved to their reservations west of the Mississippi, according to treaty stipulations.

The Kickapoos of the Vermilion were the last of the Illinois Indians to emigrate. Finally, in 1833, the last of them joined the main body of the tribe in their reservation west of Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and were afterward moved to the Indian Territory. (95)

By J.O. Cunningham / 1905

Chief Shemauger

Our early settlers around and in these timber belts and groves well remember many of their Indian visitors by name, and the writer has listened with great interest to many enthusiastically told stories from them of personal contact with these people. Particular mention was made by many of a Pottawattamie chief named Shemauger, who was also known by the name of Old Soldier. Shemauger often visited the site or Urbana after the whites came, and for some years after 1824. He claimed it as his birthplace, and told the early settlers that the family home at the time of his birth was near a large hickory tree then growing upon a spot north of Main Street and a few rods west of Market Street. He professed great love for this location as his birthplace, and the camping ground of his people for many years. At the time of the later visits of Shemauger there was not only the hickory tree, but a large wild cherry tree standing about where the hall of the Knights of Pythias is now situated. Besides these trees there were others in the neighborhood of the creek, which made this a favorite and most convenient and comfortable camping place for the Indians; and, from what is known of the habits of these people, it is not improbable that the chief was correct in the claim made upon Urbana as his birthplace. It is remembered of Shemauger that he would sometimes come in company with a large retinue of his tribe and sometimes with his family only, when he would for months in camp at points along the creek. In the winter of 1831-32, these Indians to the number of fifteen or twenty remained in their camp near the big spring on what, of later years, has been known as the Stewart farm in the neighborhood of Henry Dobson’s about two miles north of Urbana.

Another favorite camping ground of Shemauger was at a point known as the Clay Bank on the northwest quarter of Section 2, Urbana Township, sometimes called Clement’s Ford, towards the north end of the Big Grove. One early settler (Amos Johnson, who died twenty years since) related to the writer his observations of these people while there in camp. His father occupied a cabin not far away, and the family paid frequent visits to the camp out of curiosity, fearing nothing. Some of the braves amused themselves by cutting with their tomahawks mortices into contiguous trees, into which mortices they inserted poles cut the proper lengths. These poles, so placed horizontally at convenient distances from each other, made a huge living ladder reaching from the ground to a great height. Up this ladder the Indians would climb when the weather was warm and sultry to catch the breezes and to escape the annoyances of the mosquitoes. He saw the bucks thus comfortably situated upon a scaffold in the tops of the trees, while their squaws were engaged in the domestic duties of the camp on the ground below. Thirty-five or more years ago, trees from near the Clay Bank were cut and sawed into lumber at the nearby mill of John Smith, when these mortices, overgrown by many years’ growth of the trees, were uncovered, showing the work of these Indians forty years before, and corroborating the story as related to the writer.

Shemauger told another early settler (James W. Boyd, who died many years since), or in his hearing, that many years before, there came in this country a heavy fall of snow, the depth of which he indicated by holding his ramrod horizontally above his head, and said that many wild beasts, elk, deer and buffalo perished under the snow. To this fact, within his knowledge, he attributed the presence of many bones of animals then seen on the prairies.

Shemauger was remembered by those who knew him personally as a very large, bony man, always kind and helpful to the white settlers. It was also said that, upon being asked to do so, he would, with a company of followers, attend the cabin raisings of the early settlers and assist them in the completion of their cabin homes. All accounts of Shemauger represent him as kind to the whites and ambitious for the elevation of his people. One early settler (Jesse B. Webber) at the Big Grove, who came here in 1830 and remained all of that winter before making himself a home, spent much of his time in the company of the chief and formed for him a high esteem. In 1830 Shemauger was about seventy-five years of age and had, in his time, participated in many of the Indian wars with the whites and, with his experience, would gladly remain at peace with them. The Kankakee Valley was the home of the chief during the last years of his stay in Illinois, and he was seen there by those who made trips to Chicago. Following the Black Hawk War his tribe – or the remnant of it remaining east of the Mississippi River – went West and its members were seen here no more. (642-43)